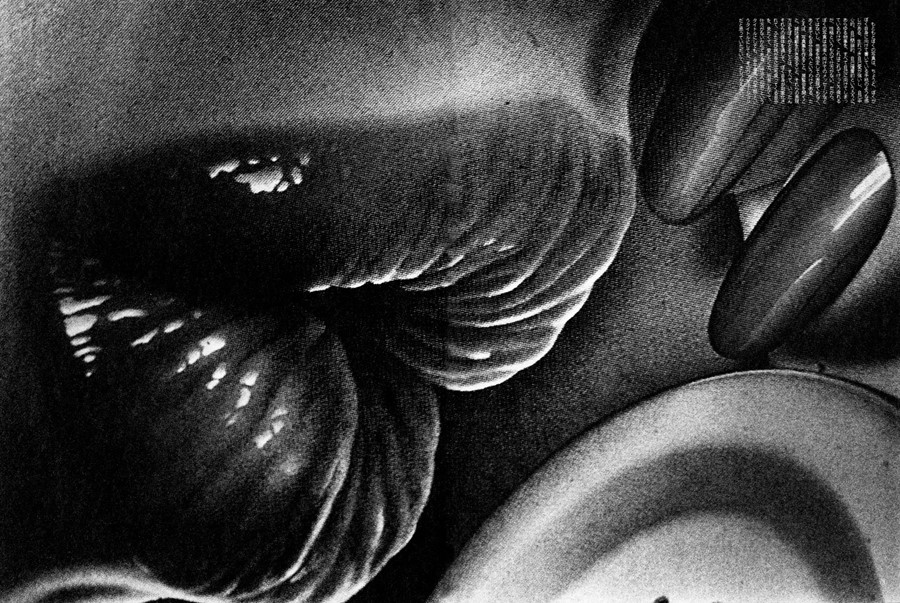

An exhilarating new book compiles the complete set of photo stories the Japanese photographer made for Shashin Jidai, the radical and experimental 1980s photo magazine that rode a fine line between photography and pornography

Daido Moriyama has been on fire this year. The great Japanese photographer took to Tokyo’s streets to lens Y-3’s new collection for AnOther, printed his photographs on toilet paper at Paris Photo and, of course, is still bowling audiences over with a major show at The Photographers’ Gallery. One of the great successes of the London retrospective is its reading room, which is packed with an array of photo books that stretch across his epic portfolio. That said, while Moriyama is indeed an inveterate bookmaker, less widely known is the fact that many of his most famous series appeared in magazines before they appeared in books. For Moriyama, as well as his peers who broke onto the scene in the 1960s and 70s, magazine spreads were like testing grounds – experimental laboratories where boundaries could be bent, broken and smashed.

Back in the mid-60s, Moriyama was virtually unknown. Having only published a few photographs in Photo Art, he was picked up by Shōji Yamagishi, the editor of the revered magazine Camera Mainichi, in which he debuted with his 1965 story Yokosuka, followed by Back Street Theatre. Announcing his jerky worldview and shoot-from-the-hip insouciance, the latter made Moriyama a star of magazine culture, so when he abruptly exited himself from the world of photography in the mid-70s, his absence was palpable. It would be several years before Moriyama would start to shoot again. However, his return was not in Camera Mainichi, but, instead, a new, alternative magazine that rode the fine line between photography and pornography.

Its name was Shashin Jidai, and its subtitle was “Super Photo Magazine”. The inaugural issue – whose 130,000 copies sold out in a flash – featured Light and Shadow, a story in which Moriyama appeared to propose photography as a descriptive device – recording flora, animals, and machinery – while breaking from the bure boke style of photography that emblematised the political strife of the 70s. It kickstarted a series of essays – or rensai – which had Moriyama working almost exclusively for Shashin Jidai throughout the 80s, sharing its pages with Noboyushi Araki as well as new kids on the block like Seiji Kurata and Keizō Kitajima. Although these essays, serialised over 63 issues, amounted to a remarkable portrait of the photographer during a crucial period in his development, they somewhat faded into obscurity after the magazine was forced to shut up shop in 1988.

On the release of Shashin Jidai 1981–1988 [published by Session Press and Dashwood Books], a staggering survey of the complete set of essays Moriyama produced for the magazine, we speak to co-publishers Miwa Susuda and David Strettell about the making of their book and what’s to admire about Moriyama.

I want to start by asking whether you both remember your first encounters with a Moriyama book? Do you have any favourites?

Miwa Susuda: My first were the three he made with Hysteric Glamour, the Japanese fashion company, in the early 90s. I remember being struck by the high contrast of black-and-white photography on glossy paper and in full bleed. I must say, they are still my favourite books by him.

David Strettell: It’s hard to pick a favourite. Bye Bye Photography, Dear, from 1972, is such a classic, inspiring book, but, like Miwa, I also loved the Hysteric Glamour series he did later. I spent some time in Tokyo in the late 80s and knew the designer, Nobu Kitmura, when Hysteric Glamour was just getting off the ground and he started to collect photo books obsessively. This was a series of completely impractical, big, floppy, oversized publications that had such an unorthodox feel to them. I’d been working with Magnum and for fashion photographers since 1985, but I’d never seen photo books quite like that. It really opened my eyes to what you could do with books and photography.

How and why did Moriyama get involved with Shashin Jidai? What was going on in his life at the time?

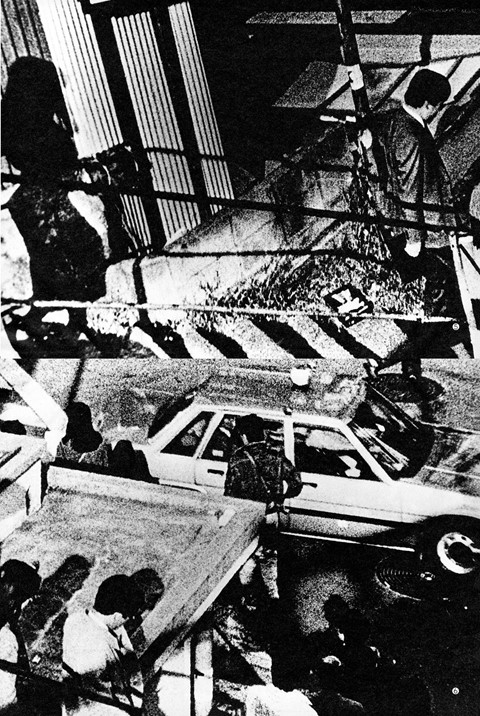

David Strettell: Well, Akira Hasegawa, one of the magazine’s editors, asked Moriyama to take part in the first issue in 1981. He had been going through some kind of a breakdown since the mid-70s. He had barely touched a camera in years and had become dependent on pills. It was a time of full crisis, and his collaboration with Shashin Jidai actually saved him.

What was different about the work Moriyama was making after his hiatus?

David Strettell: It evolved into something more polished than the very gritty urban style of the Provoke period [a hugely influential Japanese magazine from the late 1960s with which Moriyama was involved]. Moriyama also seemed more open to experimenting with subject-driven pieces.

Miwa Susuda: To me, his work was more free-spirited and totally detached from the dogmas of Provoke. You can really sense his joy and liberation.

Sourcing the full set of spreads must have been some undertaking. How did you go about it?

David Strettell: Back in 2015, I acquired a near-complete set from a dealer here in New York. From there, I worked to get the rest through a network of dealers in Japan who we work with regularly to source our rare books for the shop.

Miwa Susuda: In 2018, I went to meet Moriyama at his studio in Tokyo. We discussed our publications and I gained an understanding of his ideas about photography. He liked the proposal that all his photographs from Shashin Jidai could be compiled in one book since it had never been done before. The conversation went smoothly. As you know, there have been many Moriyama books produced in Japan and abroad. We wanted to make sure that our book was unique and special. Instead of applying the conventional hardcover, we used a mesh one, an idea that came from our designer, Geoff Han, who wanted to reference the famous stocking pictures. I love the book’s intimacy. It has a hand-made quality, kind of like a journal.

Why was it important for you to honour the original presentation of the essays and chapters?

Miwa Susuda: It was definitely important. We wanted to share Moriyama’s vision as precisely as possible. We decided to translate some of his essays across all six chapters so that Western audiences could appreciate his state of mind at the time.

David Strettell: Moriyama was very deliberate about the work he contributed to Shashin Jidai. As Miwa mentioned, there were six essays that continue chronologically through the magazine over multiple issues, each expressing different aspects of his work. It was important to see all of them in order, partly to understand what was going through his mind in real time as he began to grapple with the new style of photography that he was developing. And partly because it’s a unique document. The majority of the negatives were lost, so the magazine tearsheets are the only sources left to us.

It’s been quite the year for Moriyama. Personal highlights include his blockbuster show in London and loo roll installation at Paris Photo. What do you think keeps Moriyama obsessively making work?

Miwa Susuda: Moriyama’s legacy needs to inspire the next generation of photographers, so it’s wonderful that many institutions have consistently shown his work. For Moriyama, it seems, making work is as natural as breathing. It’s his way of living and being in the world.

David Strettell: I think for a lot of photographers whose work is, like Moriyama’s, grounded in documentary, they can’t really help themselves. The world continues to evolve around them, so there’s no other option.

How do you envisage the life of this book?

David Strettell: The main reason for the book was to bring this little-known body of work by one of the world’s most revered photographers to the public eye. It presents a pivotal period of his evolution and it’s fascinating to see how he comes to life again after his years in purgatory. It was important to include everything so the book can be used as a resource for academics too.

Shashin Jidai 1981–1988 is published by Session Press and Dashwood Books.

Join Dazed Club and be part of our world! You get exclusive access to events, parties, festivals and our editors, as well as a free subscription to Dazed for a year. Join for £5/month today.