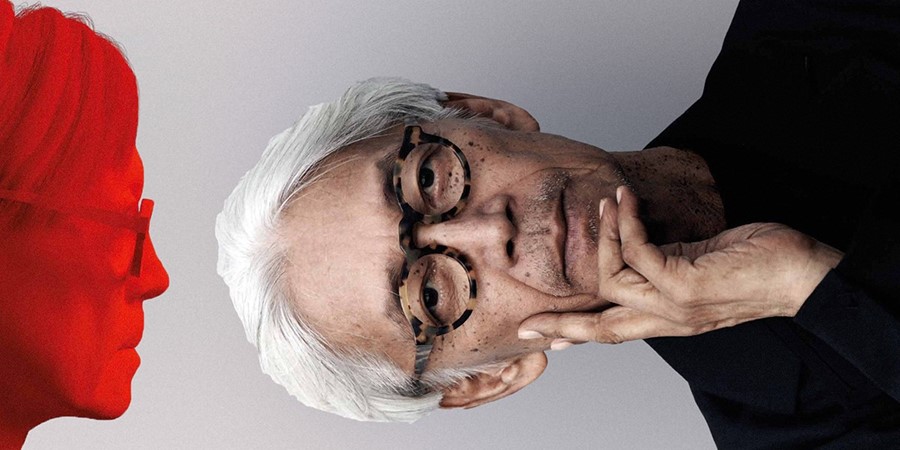

The late musician’s friend and collaborator Todd Eckert discusses his role in the creation of the new immersive experience at Camden’s Roundhouse, Kagami

“I can just kind of die now,” says Todd Eckert, reflecting on his role in creating Kagami, an immersive show at Camden’s Roundhouse that brings to life a final performance by legendary Japanese musician Ryuichi Sakamoto. Created in collaboration with the artist before his death, grief ripples through the now posthumous context of the project. But with a smile, Eckert declares that “this is not, and never will be, a memorial”.

The show is the “first of its kind”, a format that Eckert, producer of Ian Curtis biopic Control and founder of Tin Drum, a production studio and technology developer, calls ‘mixed reality’. Blending elements of live performance and AR, Kagami audiences put on special glasses that make others in attendance fade to ghostly figures, leaving you one-on-one with the artist as he plays a specially-recorded solo performance captured by 48 volumetric cameras against a green screen in Tokyo not long before his passing.

That moment in time projected in a way that feels both present and fragile – the artist vanishing between tracks – is strangely affecting. Catching up with Eckert from a grand room at the Royal Academy of Arts where his partner Marina Abromovic stages a major retrospective, we chatted about bringing Sakamoto’s performance to life, technology’s place and power in the legacy of artists and why the artist’s work still makes everyone cry.

What exactly is Kagami?

Todd Eckert: You can’t divorce the story of Kagami from its technology, but the point of the experience has never been technology. The only thing I care about is a connection between an artist who is, for me, defining in the human experience, and the audience – in this case, an audience that he’ll never meet. If you think about traditional film, it’s an artefact of something that you weren’t there to really see. Full dimensional film is the replication of the entirety of the human form presented as an event happening in real time. Usually, a director has made the decisions and we just sit back semi-anaesthetised. That’s an event happening to us, whereas with mixed reality, we think ‘oh, I wonder what’s over there’ or ‘I can't really see this person’s hand or face, so let me move over here’.

How did Kagami and your collaboration with Ryuichi come to be?

Todd Eckert: I first listened to Ryuichi’s work in the early 80s and it struck me how singular it was. There’s beauty and simplicity, but a fundamental curiosity. He played the way I wanted life to be. Watching footage of Bowie and Prince, you have no idea what it was like to see them live because their expression was so singular.

With Ryuichi, too, his relationship with a piano… it was so tender, and he accepted very high things from the instrument. It was this constant back and forth between him and it. Nobody knew how to volumetrically capture piano – it hadn’t been done. But I thought I have to get Ryuichi before something terrible happens. He had struggled with health issues for the last decade of his life.

Where did the name come from?

Todd Eckert: He and I were both just Tarkovsky freaks, so Mirror is from that originally. But we created a mirror image of Ryuichi and put it in this world.

Can you tell me about what Kagami meant to Ryuichi? Were there particular reasons for his embarking on its creation in the face of ill health?

Todd Eckert: Ryuichi was remarkably disinterested in fame. He enjoyed some of its benefits, but ultimately, for him it was all about what sound could do and how he could change it. We’d been talking about the idea for a while and he came to my apartment in New York and I showed him the work that I did with Marina. I told him my intention with this is not to just perpetuate your relationship with an audience that is already in love with you. it’s to attract people that are maybe unfamiliar with you. Actually, my ambition is to create something that will connect you with a bunch of people who haven’t even been born yet. He looked at me, and he said ‘wow’.

Kagami was created in collaboration with Ryuichi before his passing, but what’s your view on technology’s place in posthumous music and artist legacy?

Todd Eckert: I don’t, and my company will not, work in VR. VR is a process of elective isolation and we’re already in that too much with our phones. AI is ubiquitous but it’s a tool. It’s like saying, shovels are good or bad. They’re not, they’re just tools, so AI doesn’t hold any particular inspiration of fear for me. Everything that we do is about authenticity and the reality of it is you either have an original performance that allows you to authentically translate it to an audience in the future. Or you don’t and you take somebody else doing a dance and you put the head of a dead popstar on them. I have no interest in it, and I have no patience for it. There’s always been this kind of ideological fistfight between art and commerce. There are lots of reasons why the people running an estate will decide to embrace the commerce that the artist chose not to in life. That’s a question for them.

How do we both protect an artist’s creative vision and legacy after they’ve passed?

Todd Eckert: Everything that we are, as human beings, cannot be quantified by its value on a stock market or the cost of something at auction. What we are is so far beyond that. And the best that we can be after we pass, is in a series of characters or words put together on pages that explain the human condition or musical notes that give us a sense of the energy of what it’s like to be alive or to be in love.

How have audiences, including friends and family, reacted to Kagami so far?

Todd Eckert: There’s a lot of crying. There’s a fair amount of dancing. Laurie Anderson, who was a close friend of Ryuichi’s, said it was too soon for her to look him in the face, so she walked around the piano and sat herself behind his back so she could just watch his hands. I feel like this has been by far the hardest thing I’ve ever done. But in many ways, moments like that fulfil the whole reason that I did.

Laurie’s experience is interesting. Was it always the plan for audiences to be able to move around and view Kagami as they wished?

Todd Eckert: That really happened because I wanted to test it the same way that you do for say a Broadway show. The test audience started off sitting there and then they just got up and started moving towards him, like it’s the most natural thing in the world - but nobody’s ever fucking done that before.

People are aware that this is not a projection. It’s not an ABBA thing. It is an altogether different experience. At the beginning you are aware of each other, but then most of the other audience fades and it becomes a connection between you and Ryuichi.

As a friend, what part of Kagami moves you most?

Todd Eckert: I find it terrifying to watch any of this, to be honest. But I asked Ryuichi to introduce two songs, and I think, for me, the introductions are as moving as the notes that he’s playing. He’s introducing Energy Flow and he’s funny – he was super funny. He’s doing so posthumously, which was never the point, but the fact it’s happening is so moving in such a unique and complicated way.

As a fan, what does it mean to be a part of one of Ryuichi’s final projects?

Todd Eckert: It’s a bigger honour than I could have ever anticipated. I mean, I never want to present the show as a memorial. If it becomes a memorial, that’s at the choice of the audience, but I am presenting it as a new, energetic event happening right now. But there are very few times in anybody’s life that you can imagine, plot, plan and fulfil an idea of honest legacy and actually have it not screw up somewhere along the way. So, the fact that we did that is like, I can just kind of die now. You know?

Kagami is at the London Roundhouse until 21st January 2024. Tickets are available here.