Taken from the Summer 2021 issue of Dazed

One minute, Cút Lôn are pounding the stage with their high-octane thrash metal, the next they’re sharing the floor with a severed pig’s head. The pelter, whose tongue is protruding from his ‘bloodied’ mouth like Gene Simmons, surveys the scene from the mosh pit after launching the head like a fleshy hand grenade. Dressed in schoolgirl outfits and Pikachu-inspired knitted balaclavas, the four-piece band from Hanoi, Vietnam, are known for their playful antics, poking fun at everything and everyone – including themselves. “I came out of the show drenched in sweat and (fake) blood,” says one shellshocked reveller, after finding himself in the trajectory of the flying pig’s head.

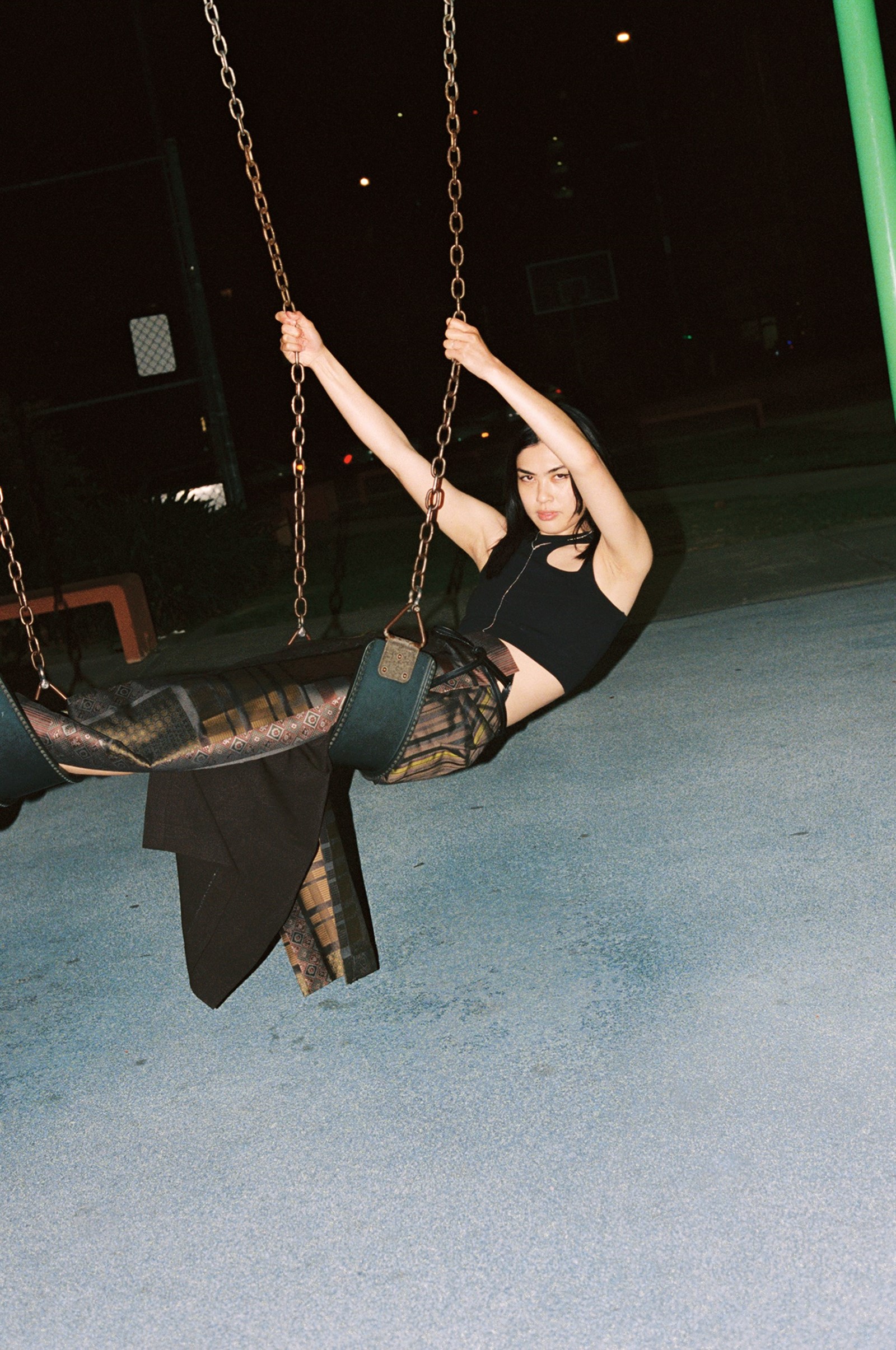

For Anh Phi, Linh Ngô, Celina Huynh, Thao Vu and Mike Pham – the founders of Ho Chi Minh City’s Gãy club night – anything is possible. Since its debut in October 2019, the night has quickly earned a reputation as the wildest rave in the city, still referred to locally as Saigon. For French-Vietnamese Anh Phi, it reflects the collective’s predilection for experimental sounds and a desire to break all the rules of the rave. (Gãy is Vietnamese for ‘broken’.) But it was also, she explains, an attempt to fill “a gap in the market and the need to develop a local rave scene”, one free from expectation. “I would often leave a club early myself, because the music didn’t quite do it for me; it just wouldn’t sustain me.”

“We wanted something inclusive, but also lots of fun,” the 28-year-old filmmaker and music producer says of the LGBTQ+ friendly night. “We don’t subscribe to convention, or at least we try not to. Gãy is a way of saying that, when everything is broken, it’s OK.” As well as standard house and techno, Gãy raves are introducing clubbers to the full spectrum of underground music largely absent from Ho Chi Minh’s club scene, from trance and psytrance to drum & bass and hardcore. For the collective, Gãy is an invitation for radical self-expression and exploration. A booming economy, coupled with the country’s largest age group – 70% of Vietnam’s population is under 35 – means that, in Ho Chi Minh, youth dominates.

Before Covid-19, Ho Chi Minh had begun to cement itself as a key destination in Asia’s underground music scene. When the pandemic struck, Gãy was able to withstand its impact better than some of the city’s biggest clubs, mirroring the fortunes of Vietnam itself. While many richer countries with solid health infrastructure floundered, the Vietnamese government acted quickly and decisively to curb the spread of the virus. As a result, the country has been able to enjoy a relatively Covid-free existence for the past year, with clubs reopening in May 2020.

“We were never in this for the money,” says Anh Phi. “Without a fixed venue and the costs attached to that, we didn’t have the financial pressure that others faced.” From the ashes of Saigon’s dancefloors, Gãy is riding a new energy. “Covid has really been an opportunity to dig deeper locally, to connect with interesting local DJs and to nurture and develop the talents of new, up-and-coming artists here in Vietnam. That, for us, has been the biggest takeaway of the pandemic.”

“Covid has really been an opportunity to dig deeper locally, to connect with interesting local DJs and to nurture and develop the talents of new, up-and-coming artists here in Vietnam” – Anh Phi

After the clubs reopened in Vietnam, Gãy was a much-needed antidote to the restrictions. “It was one of the most surreal nights of my life,” says Linh, 27, recalling the Cút LÔn party in June 2020 – their first post-lockdown event. The DJs took turns to progressively build momentum, and by midnight had whipped the crowd into a frenzy of racing punk-rock and techno. “That first night, post-pandemic, after three months of lockdown, there was definitely something different (about it),” says Linh. “People in Saigon are way more wild and expressive; they let it all out and loose. In Hanoi, they’re more composed and restrained.”

In October, the collective hosted another party at a family-run guesthouse in a typically Vietnamese narrow, multistorey building on Bui Vien Street, a notorious pedestrianised strip crammed with hostels and 24-hour bars that would normally be teeming with backpackers. After months of stasis and business strain, the restaurant was more than happy to host a rave. “It was a win-win situation,” reflects Linh.

For all their emphasis on hedonism, the Gãy team have ambitions beyond the dancefloor. The loss of a close friend to suicide spurred the group to partner with InPsychOut, a mental health charity run by young psychologists. The collaborative podcast offers Vietnamese youngsters a vital mental health forum, with most listeners aged 18–24. “None of us in the collective is qualified beyond talking about our own experiences, which is why it was important to collaborate with people who are,” explains Linh. “[Discussion around] mental health in Vietnam remains taboo – our parents don’t think it’s real, even though many in our creative community have experienced depression. If I tell my mum I’m depressed, she’ll just tell me to get over it or to keep busy.”

“There aren’t a lot of facilities here and the few that are most people can’t afford,” says Anh Phi. Depressive disorders in Vietnam account for 5.7% of the disease burden, according to the World Health Organisation. Meanwhile, the government estimates that around 15% of the population requires specialist mental healthcare. Proceeds from the collective’s first club compilation, released on their own Nhac Gãy label, were donated to InPsychOut on its release in February.

Just as the Cút Lôn party opened up the pressure valve on a locked-down city, Gãy’s physical and emotional safe spaces are helping a new generation of Vietnamese clubbers connect through music, swapping social isolation with a sense of belonging. “We’re all misfits,” says Linh. “At Gãy, we celebrate that.”