Simon Wheatley has spent a career capturing the key players of grime. Bound, his new exhibition and zine, explores the spirit of resistance vital to the genre

If there’s one photographer who really knows grime, that person is Simon Wheatley. He’s been on the ground since the beginning, capturing unguarded moments from the key players of the scene – but doesn’t always like to call it that. “I’ve never really been interested in any ‘scene’”, he tells Dazed. “I actually find the whole concept of ‘scenes’ limiting. They end up being uncreative places once everyone jumps on.” Instead, Wheatley prefers to think of grime as a ‘moment in time’, one where political expressions of angst were not only as important as the music, but the reason the music exists in the first place.

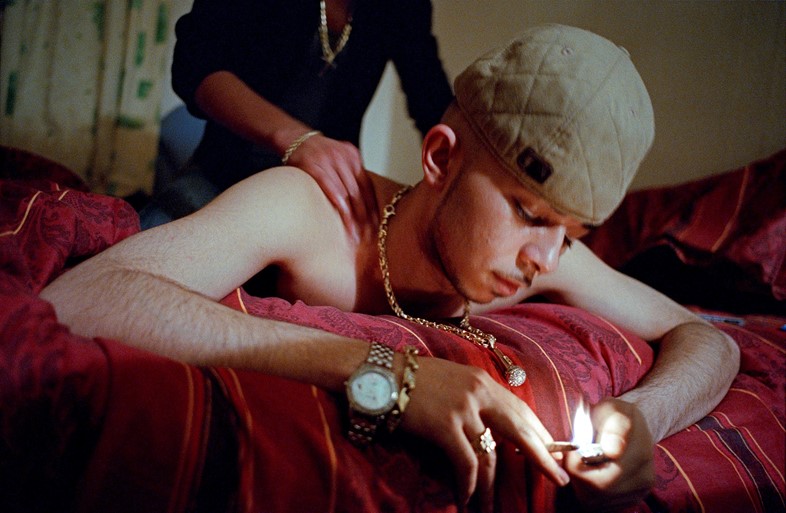

Political currents have always run through Wheatley’s work. His 2011 photo book Don’t Call Me Urban! The Time of Grime acted as an antidote to the glamorisation of “urban” life, while his 2016 documentary film Goldenboys charted grime’s second wave, away from the commercialisation that had erupted in recent years. Now, for 2023, the photographer continues that political mission, presenting a collection of photographs that capture grime’s spirit of resistance. Taken between the years of 1998 and 2015, Bound is a zine that chronicles the behind-the-scenes moments of London’s grime heartlands, from the nappy changes, to the dog walks, and the tower blocks that no longer exist.

In the conversation below, we chat to Wheatley about his artistic practice, the commercialisation of grime, and why political resistance is a key component of the genre.

Hi Simon. Congratulations on the publication of Bound. How long have you been capturing the Grime scene, and what led you to becoming involved?

Simon Wheatley: I’ve never really been interested in any ‘scene’. I actually find the whole concept of ‘scenes’ limiting. They end up being uncreative places once everyone jumps on. Grime struck me as a moment in time. I had been photographing the youth on London’s council estates for five years when this new sound emerged like a soundtrack to pictures I had been making. So I saw it as something on a sociological level, a powerful expression of alienation and angst.

Fortuitously, I started to work for Rewind magazine and obtained a lot of access. I came across most of the prominent crews and as I was living in east London I was just about, rolling with the younger kids who frequented the youth clubs – which were the original grime underground. The kids interested me far more than whoever was becoming famous.

Did you also photograph grime’s second wave?

Simon Wheatley: I was also around when it had its resurgence around 2014, but that wasn’t anywhere near as interesting as the original grime days. For me, what I had known as grime didn’t really exist anymore. Most of the youth clubs had closed, there was no pirate radio and some of the iconic estates had been demolished or transformed. Brands and their PR companies had taken over the scene, and the audience was more Dalston and Shoreditch than Bow and Plaistow – more middle-class and white.

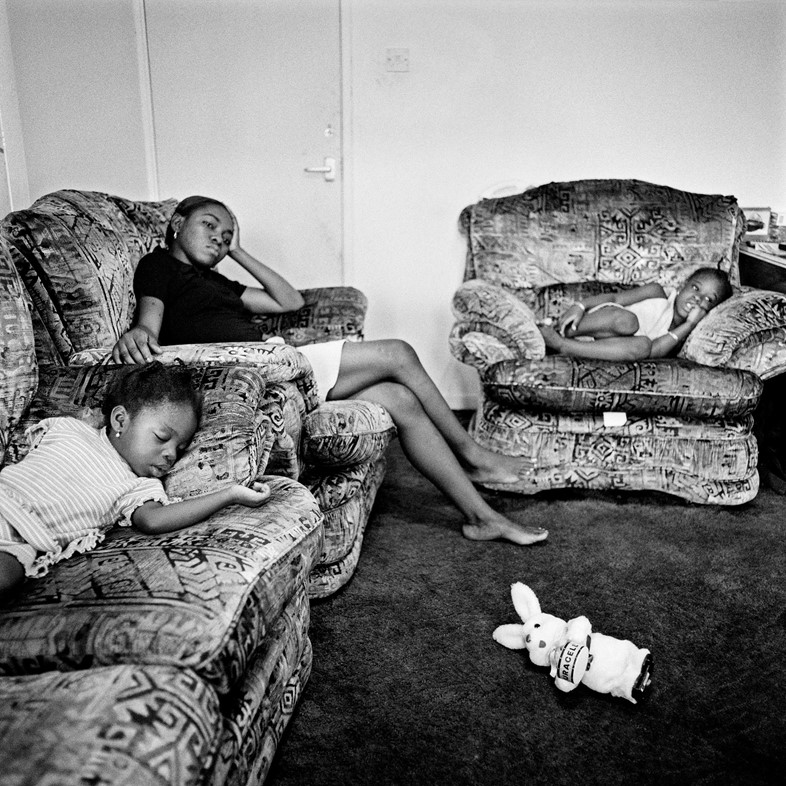

I was making a film about The Square – the most instrumental crew in that resurgence – and was fascinated by the contrast between the shallowness of mainstream hype and the way the roots of the music were still in that raw and vulnerable social place. Sometimes I would take a break from filming and take a few pictures, and in Bound there are some shots of The Square and also a touching moment when Elf Kid is at home with his brother and sister, checking Twitter reactions of his smash hit ‘Goldenboy’, which had dropped a few minutes earlier. And I’m still around photographing, whatever the genre might be called.

Was there an exact moment of inspiration that led you to create Bound?

Simon Wheatley: Bound came about from a session with the curator after I was approached by Bernie Grants Arts Centre to exhibit there. I showed him a wide edit of pictures for a big book I had in mind, covering the long years of my involvement on London’s council estates. I liked the way he was honing in on pictures where people come together and hold on. He went for the outtake from my famous Crazy Titch shoot because of the manner in which Titch was grasping the dog.

In Debo Amon’s introduction to the zine, he outlines the importance of ‘building communities of resistance’ and adds that grime is an ‘artistic act‘ of that resistance. How important is this concept to your artistic practice?

Simon Wheatley: It’s fundamental. I first became interested in photography when I saw Sebastião Salgado’s pictures of the mines in Brazil – I’d just been at university there as part of my degree. I was searching for some purpose in life and I found it in those pictures and also in the character of Salgado himself, who had been exiled by Brazil’s military government as a young economist in the sixties. I also studied a lot about the American civil rights movement at university and my interest in rap came about through that, being black America’s voice of protest and discontent. All the books of my photography are very political.

Do you prefer to set up the shots or capture the subjects as they are?

Simon Wheatley: The only set-up shots in the exhibition are the ones shot on a 6x7 medium format camera, the portraits of music personalities. I prefer not to set up pictures otherwise and be faithful to the truth of a situation, whatever it may be. I’ve always shot my reportage on 35mm cameras, so there’s been a fundamental distinction in my work based on what camera I use.

The photographs are at times extremely intimate and personal. Did you ever feel like you were intruding?

Simon Wheatley: Intimacy is important to me, I always search for it. I’m very emotional. I learned that a documentary photographer should have an antenna to feel out situations, to know when to go. There are no situations in the exhibition in which I felt unwelcome – I never felt I was intruding. Often we would be having deep conversations and I’d just make a few frames here and there.

If you could choose one image in the series, that is either your favourite image or representative of the project as a whole, which one would it be and why?

Simon Wheatley: There’s no one representative picture. I feel Bound is a collection of images. But looking through the fanzine, the picture that touches me most emotionally is the square black and white one of the guys standing on a walkway that was demolished the following winter. I don’t think it’s the best photograph necessarily, but it reminds me of a more innocent time – when ‘youth’ didn’t begin at the age of 12, when guys didn’t feel the need to look so tough like they do now with drill culture, before the corruption of smartphones and social media.

I didn’t know those guys so well, but there’s a warmth in the way they look at me. It’s like a prophetic welcome from those first days of my London work back in the early summer of 1998. In their smiles and grins I see now, perhaps, the secret to my success, the way people might find me amusing.

Is there anything about London specifically that inspires you?

Simon Wheatley: I find London overly materialistic and people can be cold. I always ran away from England in search of somewhere else because of my teenage traumas. But finally, after a decade in India trying to find someone I might never be, I have come to accept London as my home, largely through the love I have had from those in my pictures and the people who have grown up with my work. I would say that inspires me, the love I now feel from the younger generation. It gives me the strength to continue, to find new paths ahead, to not just sit back in the glow of my previous work, but to use it as the basis for further endeavour.

What would you say is the guiding principle behind the work?

The search for truth, and having some fun along the way.

Bound exhibition is open at Bernie Grants Arts Centre, Tottenham, London, N15 4RX until January 31, 2024. The Bound zine launches at Claire de Rouen Books, Bethnal Green, London, E2 0JD at 6pm on December 13, and is available to purchase here via Backdoor Editions.

Join Dazed Club and be part of our world! You get exclusive access to events, parties, festivals and our editors, as well as a free subscription to Dazed for a year. Join for £5/month today.