In a rare interview, Japanese musician Joe Hisaishi reflects on creating the soundscapes for Studio Ghibli and why music should radiate raw emotion

From the courageous pirates-chasing-rainbows-beyond-the-clouds spirit that underpins 1986’s Castle In The Sky to the strangely soothing growing pains of 1988’s My Neighbor Totoro, director Hayao Miyazaki’s films for the pioneering Studio Ghibli have transformed animated storytelling for the better. And much like Alfred Hitchcock and Bernard Herrmann or David Cronenberg and Howard Shore, the auteur of anime has tended to rely on one specific musician to give sonic meaning to his masterpieces.

Joe Hisaishi is the composer responsible for the symphonic poetry present in all 11 films the Studio Ghibli maestro has directed over the last 40 years. The carefully considered space between Hisaishi’s notes builds a palpable tension that demands your full attention, ensuring you’re willing to invest 100 per cent in the idea of a grinning Catbus or a talking heron (more on that later) lighting up the cinema screen.

Hisaishi’s soaring violin arrangements, which replicate the stomach-raising feeling of taking full flight amid a biblical gust of wind and swarming enemies, and also the ancient romance of his nostalgic keys, have not only inspired a million and one video game soundtracks (see Streets of Rage or Zelda), but they’ve played a pivotal role in making us feel so attached to the eccentric rotating cast of Miyazaki-directed characters. It’s as if we have heard their inner voice through Hisaishi’s music; an intimate experience that brings you closer together and just might be the reason so many people have Studio Ghibli characters tattooed on their bodies.

Studio Ghibli movies tend to conjure up life-affirming feelings for audiences, all despite dark subject matter that grapples with heavy concepts like the fragility of our natural world (Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind) and life after death (Spirited Away). Therefore, Hisaishi’s minimalist yet heartfelt compositions function as a crucial cushion (take “Path of the Wind” and its glockenspiel-flute combination that glistens with the warmth of a hug from your grandmother); a welcome relief from the inner turmoil that usually follows the cutesy characters as soon as the sunny opening credits finish rolling.

His soundscapes are so important to the feel of a finished Studio Ghibli picture that the studio often asks for his final compositions during early pre-production, ultimately letting his music guide the directing and writing process. However, when you ask Hisaishi the secrets behind such a rich, long-lasting collaboration (and those 11 beloved Studio Ghibli scores for Miyazaki), his humble response is far removed from the mystical philosophy that fuels the actual films.

“I think the secret to a long-lasting professional relationship is not having too much of a personal relationship,” Hisaishi tells Dazed in an early morning phone call, via a translator. “Me and Hayao don’t go out to eat or drink together. We’re strictly professional.” Of his own approach to composing, he adds humbly, and with an endearingly croaky laugh: “I am a basic, simple composer. I only want to compose things I can easily play at home on my piano.”

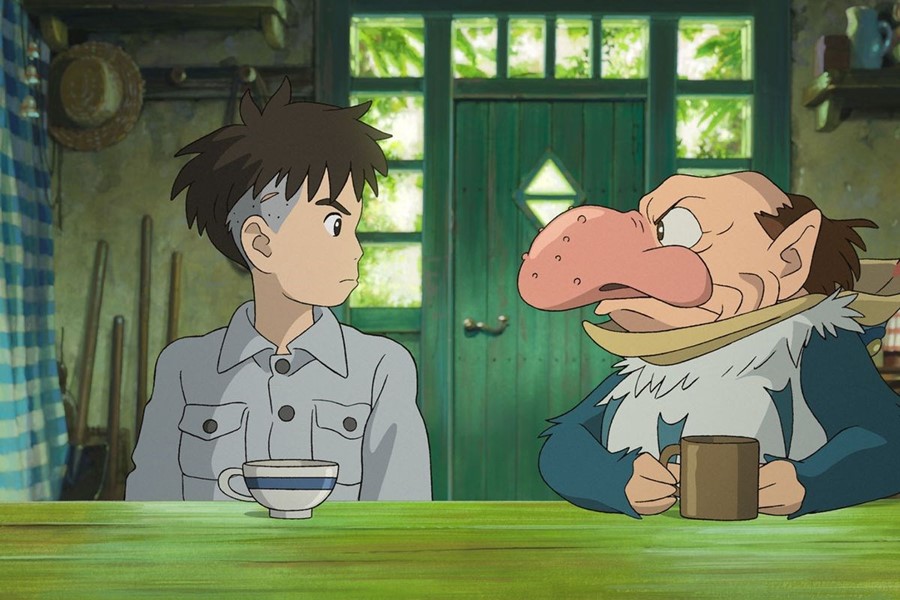

Hisaishi’s latest Miyazaki collaboration, The Boy and The Heron, is about a teenage boy who longs to be reunited with a dead parent. It is set during a war-torn Japan and partly channels director Miyazaki’s own regrets about the things he never got to say to his late mother. In this Oscar-tipped film, young Mahito (voiced by the impressively empathetic Soma Santoki) moves to the countryside, where he’s bullied at the local school and given an offer to be reunited with his mother by a mysterious bird that claims to be able to fly through alternate realities.

The film’s music carries an aching melancholy, particularly the “Sanctuary” arrangement and its strings that sound like a matriarch weeping; the sadness and scale of loss present in a haunted, WW2-era Japan seems to be channeled directly through Hisaishi’s playing. The score also reflects the fevered rollercoaster ride of adolescence, containing skittery keys (“Reincarnation”) that mirror Mahito’s senses gradually stirring back to life and a smile returning to his anguished face upon realising death isn’t something he should ever fear.

“This score was all about the young boy and the inner conflict he had to bear,” explains Hisaishi of the abrupt switches between contemplative sadness and soulful glory he achieves during The Boy and The Heron’s score. “I focused on his raw emotions rather than anything political.”

It’s been a landmark year for Joe Hisaishi. As well as his work for The Boy and the Heron (which capped off 50 years of helming film scores), his compilation album A Symphonic Celebration: Music from the Studio Ghibli Films of Hayao Miyazaki was a classical bestseller, racking up more than 75 million streams globally. Hisaishi also played sold out stadiums across the world, including London’s Wembley Arena. Even though he admits playing live “takes energy away” from writing original music, it’s clear the musician is savoring a lot of the recognition.

Raised in Nakano, Nagano, Hisaishi started violin lessons at the age of five and would later graduate from the prestigious Kunitachi College of Music. “My father was an ordinary high school science teacher who loved chemistry,” Hisaishi, dubbed “the John Williams of Japan” by Pitchfork, recalls of his childhood. “Dad wasn’t really familiar with music, but he did love the cinema. He took me to the cinema to see hundreds of films.”

From here Hisaishi developed the dream of composing film scores himself and, although he broke through with abstract, dream-like electronic compositions via 1981 solo album MKWAJU, he organically progressed into orchestral work and serene collaborations with film directors like Isao Takahata and Takeshi Kitano. In the early 1980s, the man born Mamoru Fujisaw adopted the name “Joe Hisaishi” (based on the kanji translation of “Quincy Jones”), and this reference to the legendary Thriller producer was a clear nod to the funk, soul and jazz leanings rooted in his sound.

“In my life, I just want to make music that can make people happy and escape” – Joe Hisaishi

These roots are evident on the “Ending Theme” for My Neighbor Totoro, which has a disco-channeling upward swing and vocals so jolly (from guest singer Azumi Inoue) that they absolutely nail how this classic film forces you to see through the carefree eyes of an innocent child and harmless dancing, hairy nocturnal beast. Compared to those early days in the music business creating these beloved songs, Hisaishi accepts modern music is now a lot less led by live instrumentation and more tech-driven.

The orphaned, stone-holding farm girl Sheeta from Castle in the Sky has a famous quote: “No matter how great your technology might be, the world cannot live without love.” As a classically trained musician, I ask Hisaishi whether he believes the rise of artificial intelligence and more computer-led music programming has taken some of the purity out of music. Moving forward, is that an active fear? “Technology advancing is inevitable. Computers become more sophisticated, and then there’s AI like ChatGPT; there is just no way of stopping it,” he replies. “What is important is what parts do we take from this technology, so humans can coexist with it.”

He continues: “I am a realist, so I don’t think like Sheeta that love is so unique it can save the world or anything like that. But I do think it is really interesting, that in the 21st century and with all this information being shared and all this technology advancing, we still have countries like Russia and Ukraine fighting a war in a basic and old fashioned way. Maybe there’s certain things technology can’t provide. [With or without modern technology], in my life, I just want to make music that can make people happy and escape.”

My personal favourite Joe Hisaishi song is “One Summer’s Day” from Spirited Away, where a meandering piano melody makes it feel like you’re flipping through a book of historic family photos on a reflective and sunny Sunday afternoon in a garden awash with purple tulips. It carries a poignant stillness and the introduction of cascading, floaty strings and bird song-like flutes nails how Spirited Away is intrinsically a film about the strange freedom and hope death can grant us. The lightness after shedding our bodies and taking on a new form is so crucial to the film’s story and this is something the composer, who has somehow never won an Oscar for this work, seemed to understand on a deep compositional level. It’s impossible not to get goosebumps while listening to this particular song, which even inspired an underrated Lil B remake.

Given how the aforementioned Spirited Away and The Boy and The Heron both present such deep meditations on death, I wonder if Hiashi believes in an afterlife himself, and if the theme of mortality is ever a musical inspiration, like I suspect it to be. “It isn’t uncommon in the Asian way of thinking to believe in [animal] reincarnation,” he answers. “I feel like when we die in this lifetime, well, that is the final end. That’s how I choose to live. I life this life to the fullest, as I know everything stops when you die.”

His most famous collaborator, Hayao Miyazaki, has repeatedly spoken about retiring, before ultimately changing his mind and returning back home to filmmaking and animation. And, as our call winds down, I ask Joe Hisaishi, who is now 73, whether he would ever consider putting his musical notebooks in the cupboard and calling it quits for good. With an uncharacteristic sting entering his voice for the first time, something which suggests Father Time might just be a mortal enemy, the legendary composer says: “When watching Mr Miyazaki say he would retire, I’d always say: ‘no way!’ I just don’t believe in it.”

So long as the 82-year-old Miyazaki is down, you sense he can rely on Hisaishi to answer the call and keep creating Studio Ghibli scores. But with or without his creative muse in tow, Hisaishi is inspired to keep on working with new collaborators. “Honestly, I think I will compose music to the day I die,” he concludes with the passion of someone only just entering their peak years. “I won’t retire ever! I love creating far too much.”

The Boy and The Heron is in cinemas now. Joe Hisaishi’s A Symphonic Celebration is available to stream, released on Universal and Deutsche Grammophon.